By Wilson da Silva

A new solar cell configuration developed by engineers at the University of New South Wales has pushed sunlight-to-electricity conversion efficiency to 34.5% – establishing a new world record for unfocused sunlight and nudging closer to the theoretical limits for such a device.

The record was set by Dr Mark Keevers and Professor Martin Green, Senior Research Fellow and Director, respectively, of UNSW’s Australian Centre for Advanced Photovoltaics, using a 28-cm2 four-junction mini-module – embedded in a prism – that extracts the maximum energy from sunlight. It does this by splitting the incoming rays into four bands, using a hybrid four-junction receiver to squeeze even more electricity from each beam of sunlight.

The new UNSW result, confirmed by the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory, is almost 44% better than the previous record – made by Alta Devices of the USA, which reached 24% efficiency, but over a larger surface area of 800-cm2.

“This encouraging result shows that there are still advances to come in photovoltaics research to make solar cells even more efficient,” said Keevers. “Extracting more energy from every beam of sunlight is critical to reducing the cost of electricity generated by solar cells as it lowers the investment needed, and delivering payback faster.”

The result was obtained by the same UNSW team that set a world record in 2014, achieving an electricity conversion rate of over 40% by using mirrors to concentrate the light – a technique known as CPV (concentrator photovoltaics) – and then similarly splitting out various wavelengths. The new result, however, was achieved using normal sunlight with no concentrators.

Dr Mark Keevers and Professor Martin Green of UNSW’s Australian Centre for Advanced Photovoltaics.

“What’s remarkable is that this level of efficiency had not been expected for many years,” said Green, a pioneer who has led the field for much of his 40 years at UNSW. “A recent study by Germany’s Agora Energiewende think tank set an aggressive target of 35% efficiency by 2050 for a module that uses unconcentrated sunlight, such as the standard ones on family homes.

“So things are moving faster in solar cell efficiency than many experts expected, and that’s good news for solar energy,” he added. “But we must maintain the pace of photovoltaic research in Australia to ensure that we not only build on such tremendous results, but continue to bring benefits back to Australia.”

Australia’s research in photovoltaics has already generated flow-on benefits of more than $8 billion to the country, Green said. Gains in efficiency alone, made possible by UNSW’s PERC cells, are forecast to save $750 million in domestic electricity generation in the next decade. PERC cells were invented at UNSW and are now becoming the commercial standard globally.

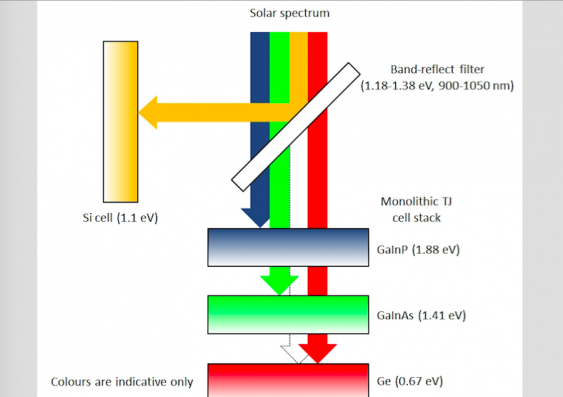

The record-setting UNSW mini-module combines a silicon cell on one face of a glass prism, with a triple-junction solar cell on the other.

The triple-junction cell targets discrete bands of the incoming sunlight, using a combination of three layers: indium-gallium-phosphide; indium-gallium-arsenide; and germanium. As sunlight passes through each layer, energy is extracted by each junction at its most efficient wavelength, while the unused part of the light passes through to the next layer, and so on.

A diagram of the spectrum-splitting, four-junction mini-module developed at UNSW.

Some of the infrared band of incoming sunlight, unused by the triple-junction cell, is filtered out and bounced onto the silicon cell, thereby extracting just about all of the energy from each beam of sunlight hitting the mini-module.

The 34.5% result with the 28 cm2 mini-module is already a world record, but scaling it up to a larger 800-cm2 – thereby leaping beyond Alta Devices’ 24% – is well within reach. “There’ll be some marginal loss from interconnection in the scale-up, but we are so far ahead that it’s entirely feasible,” Keevers said. The theoretical limit for such a four-junction device is thought to be 53%, which puts the UNSW result two-thirds of the way there.

Multi-junction solar cells of this type are unlikely to find their way onto the rooftops of homes and offices soon, as they require more effort to manufacture and therefore cost more than standard crystalline silicon cells with a single junction. But the UNSW team is working on new techniques to reduce the manufacturing complexity, and create cheaper multi-junction cells.

However, the spectrum-splitting approach is perfect for solar towers, like those being developed by Australia’s RayGen Resources, which use mirrors to concentrate sunlight which is then converted directly into electricity.

The research is supported by $1.4 million grant funding from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), whose CEO Ivor Frischknecht said the achievement demonstrated the importance of supporting early stage renewable energy technologies.

“Australia already punches above its weight in solar R&D and is recognised as a world leader in solar innovation,” Frischknecht said. “These early stage foundations are increasingly making it possible for Australia to return solar dividends here at home and in export markets – and there’s no reason to believe the same results can’t be achieved with this record-breaking technology.”

He noted that the UNSW team is working with another ARENA-supported company, RayGen, to explore how the advanced receiver could be rolled out at concentrated solar PV power plants.

“With the right support, Australia’s world leading R&D is well placed to translate into efficiency wins for households through the ongoing roll out of rooftop solar and utility-scale solar projects such as those being advanced by ARENA through its current $100 million large-scale solar round, he added. “Over the longer term, these innovative technologies are also likely to take up less space on our rooftops and in our fields.”

Other research partners working with UNSW include Trina Solar, a PV module manufacturer and the U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

This article was originally published at UNSW.edu.au.